By Katie Harris

I’ve developed a new relationship with air quality this summer. Looking at a national newspaper’s online map every few days, I watch the Canadian wildfire smoke waft back and forth, covering New York and then Chicago, drifting down to settle in our Blue Ridge Mountains. I check the numbers on Wunderground. I think I can feel the particles as I breathe on top of Cedar Rock on a Code Orange day, but it’s just a psychological trick.

I’ve also developed a new appreciation for wildland fighters, and how different contexts (thousands of forested acreage devoid of humans in Quebec versus a state forest in the heart of a residential community, for instance) call for different strategies.

Dupont State Forest engages in controlled (or prescribed) burning at set times during the year when a fire will not pose a threat. Those lucky enough to live here in the spring may remember a certain week when competing burns occurred in Pisgah National Forest and Dupont State Forest. A string of perfect weather days made chokingly uncomfortable.

But there is a benefit to these prescribed fires, accordingto Assistant Forest Supervisor Mike Santucci. “Fire has been a historical part of the ecological system, and a necessary natural process to maintain the health and resiliency of the forests on DuPont.” No fire means less diversity of species as well, including wildlife.

By now, American foresters have learned lessons the hard way when it comes to fire suppression, particularly out West. In the late 1800s, Yosemite’s Board of Commissioners condemned the periodic burning practices of indigenous peoples; John Muir wrote that fire was the “arch destroyer of our forests, and sequoia forests suffer most of all.” Always confident, that John Muir. But sequoia seeds rely on fire, and indigenous practices are becoming more and more respected when it comes to land stewardship.

Our western culture is slowly learning to let the ecosystem function in the way it has evolved to function. But this process is complicated by the presence of humans. Wildfire damages homes; sometimes it claims lives. People would prefer to avoid fire at all costs, much like their Yosemite-managing predecessors, but now we know that a history of controlled burning actually mitigates wildfire damage when a fire does get out of control.

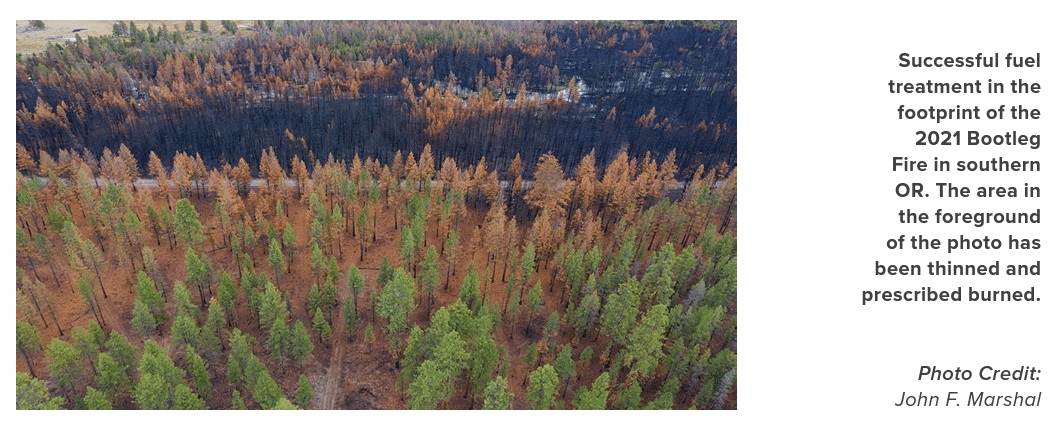

“Increased fuel loads created by decades of fire suppression create conditions for more catastrophic wildfires when they do occur,” says ecologist Joe Lovenshimer. The concept is dramatically illustrated in the photograph below, taken after Oregon’s Bootleg Fire in 2021.

If you’ve ever had the chance to visit an area after a broadcast controlled burn, there is a visible payoff to forest health. It reminds me of how my hair feels after a good trim. See the way wild blueberries thrive after the rhododendron and mountain laurel have been cleared out a bit. A hillside of ferns instead of a nondescript slant of bramble. Heightened contours on the grain of charred trunks.

Historically, the land thrived with frequent, low to moderate intensity fire across the landscape. “That is what we are trying to mimic on DuPont,” shares Santucci. This type of fire is different, of course, from the high intensity wildfires that have recently swept across California and Oregon, damaging hundreds of homes and scarring the land.

The controlled fires in Dupont help sustain “open forests and woodlands with savanna-type understories, pine-oak heaths, and even more closed oak-hickory forests, to name a few.” No animals are harmed, and some species especially thrive, such as the Table Mountain pine (pinus pungens). This particular tree, native to the Appalachian Mountains, requires fire for the cones to open and the seeds to fall on the ground. Controlled burning brings age diversity to the forest as well, mimicking the natural process of the forest replacing itself as it ages and older trees die from pests, blowdown, disease, and potentially wildfire.

Returning to my memory of the smoke-filled week last spring, I asked Mike Santucci when to expect these controlled burns.

“There are two distinct ‘burning’ seasons: fall and spring.” The fall season typically runs from early November to mid-December, and the spring runs mid-March til late April. “That said,” Mike shares, “the thing to keep in mind is that not every day during the burning season is available for us to burn. We are looking for ‘windows’ with very specific temperatures, humidities, and wind speeds and direction that will allow us to control the intensity of the fire.”

I also asked if Dupont State Forest ever coordinated with Pisgah National Forest on specific burns, taking turns perhaps. Mike shared that the two agencies do not coordinate on specific burns, but they do occasionally share resources with each other. “Generally speaking, if burning conditions are good for DuPont, they are good elsewhere around the area and there can be a scarcity of resources.”

He went on to share that Dupont has coordinated and collaborated with several partner agencies in the past, such as Southern Blue Ridge Fire Learning Network and the Forest Stewards Guild. Of interest, the Forest Stewards Guild provides “Learn-and-Burn” opportunities for landowners and others interested in how fire is applied appropriately. They observe a live prescribed burn “in action.” If anyone in Friends of Dupont Forest is interested in a practical prescribed burning learning opportunity, they should contact Dakota Wagner at The Forest Stewards Guild.

In closing, expect to see prescribed burning in Dupont during the fall and spring seasons, but know that the inconvenience of a closed trail or smoky afternoon ensures a thriving, diverse, and more resilient forest for years to come.